By: The late Ronny J. Coleman, Fire Chief (Ret.)

In doing some research online regarding firefighter safety, I came across this “oldie but goodie” from one of the legends of the fire service in the U.S., the late Ronny Coleman. For firefighters and officers of a certain age, we grew up with Chief Coleman particularly as we read his classic monthly column in the old Fire Chief Magazine (the hard copy), The Chief’s Clipboard.

For me, reading that column provided my first real taste of officer development as I’d just been promoted to a company officer position in my department, the Chesterfield (Va.) Fire and EMS Department, nee the Chesterfield Fire Department. This was one such column.

October 1, 2005

A term that has come to express the essence of a victim surviving a medical emergency is the Golden Hour. Contained in that catchy phrase is the idea that if you can’t do all of the right things to an injured or very sick person within the first 60 minutes of being called to the scene, the chance of a successful outcome deteriorates rapidly. It’s a good phrase. It’s succinct; it’s clear; it implies value through the use of the word “golden.”

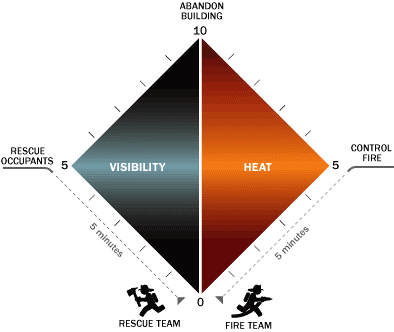

Well, chief, what’s the corollary phrase for our core mission, firefighting? Do you have one, and does it connote value? I would like to suggest that a hypothetical diamond exists on every fire. It isn’t one made from carbon under pressure, but it certainly has a high price tag. It looks like the figure below.

Perhaps we can begin to evaluate what I call the Diamond Time of Firefighting. You see, fire isn’t as forgiving as a medical emergency. There’s a period of time, usually about the first 10 or 15 minutes of a fire unit being on scene, when the vast majority of truly effective firefighting and rescue operations occur. Once a fire goes beyond that first “burning” period, things can deteriorate quite rapidly. Firefighters can get hurt. Fire losses increase very rapidly.

On an EMS call, we’re there to stabilize the situation. When we arrive on a fire, it’s going from bad to worse as fast as it can. For some time now there has been an acceptance of the idea that most fire agencies respond to EMS calls at a rate of 10 to 15 times more frequently than we respond to structural fires. That’s very true. Look at your own data. What is your own experience?

Some say that this phenomenon is reducing the ability of firefighters to deal effectively with bad fires. Let’s not forget, however, that reducing the number of times we go to the scene of a structural fire doesn’t reduce the consequences of not being able to make a difference in the outcome once we are called to one. In other words, not having a lot of big fires isn’t a reason to be unable to deal effectively with the next big one you have.

The probability of a fire occurring at any point in any 24-hour period is very real. We haven’t reached the level of statistical sophistication where we can predict our next fire, much less our next big one. Moreover, every single fire in a structure has the potential of growing to the point that it will destroy that structure once the fire reaches the open flame stage, achieves flashover and extends beyond the room of origin.

Don’t worry, I’m not going to repeat the old discussion of the time–temperature curve or flashovers. You already know about those things. We already know that it is a formula for disaster. So, what is there to discuss?

Over the last decade, we have seen a great deal of dialogue about response times. More and more we recognize that if a fire resource isn’t dispatched in a timely manner, then a negative consequence should be expected. This discussion has centered on the three basic elements of (1) the dispatch center notifying the fire department, (2) the stations mobilizing and responding, and (3) the department’s resources traveling in a timely manner.

Again, let’s not be redundant. If you haven’t been part of the discussion of this debate for the last five years, you either have more than enough stations and apparatus, or you don’t have a real fire problem. I’m not going to go down that path, either.

What I am proposing is that we accept there’s a 10-minute window after we arrive on scene that really determines whether we’re going to make a difference in the outcome of a fire in a structure. It is a 10-minute period only. This is the idea we need to get our fire officers to clearly understand. Just like the Golden Hour, the first 10 minutes is vital to their safety.

The way this diamond works is fairly simple. Many discussions of travel times and deployment analysis include the concept of critical tasking, the number of personnel we need on the scene to handle the problem. No matter how many fire apparatus we send to the scene, it’s the people who have to do two very specific things if we want a successful outcome in a structural fire. Firefighters have to make sure everyone is out of the building, and they have to find the seat of the fire and put it out. Right?

Simple enough. But let’s consider the consequences of time on that obligation. Imagine that you, as part of a fire crew, arrive on scene and can perform neither of these tasks for 15 minutes. You’re outside; the victims are inside. The fire is potentially growing, and you have no idea of where it is or what it’s doing.

What degree of success do you have in effecting a positive outcome in this scenario? If you’re an experienced fireground officer, you will probably have to admit that the outcome is going to be undesirable.

I would guess that some of you have already experienced that frustration. Early in my career I responded on a fully involved single-family dwelling that was only about 100 yards from my fire station. We could actually feel the radiant heat when we opened the station overhead doors. We could see as if it were dawn at 03:30. Response time was in seconds. The building went to the ground and a woman died. She was dead before we ever left the station.

In another scenario I responded to a fire in a supermarket where smoke conditions were so intense we couldn’t see our own hands on the shutoffs of the nozzles that we were trying to drag into the interior. We went so far into the building we could hear the fire, but we couldn’t see where it was until a truck company opened up the building. It actually took about 30 minutes, but it seemed like an eternity.

The Diamond Time Theory is based on two ideas. The first is that if you can’t find victims in the first 10 minutes, their ability to survive decreases very rapidly. Simultaneously, if fire crews are on the inside trying to find both the victims and control the fire, they can only do one at a time, or there have to be several people working concurrently. If the victims haven’t been located and you don’t have control of the fire, then the danger to firefighters increase as rapidly as survival chances of victims decrease. They’re reciprocals of each other.

Look at the Diamond Time figure again. Did you notice the one-minute increments? They aren’t arbitrary units. They’re tick marks on the time continuum that are real, measurable and irrevocable. They pass whether you care or not. They pass regardless of whether you’re making progress.

At the bottom of the diamond is the point of departure. It’s zero time. You’re on scene, you can see what the emergency scene looks like. The clock is ticking. You have two choices. Go in, stay out. If you go in you have two choices: find the people, find the fire. Stay out, you risk nothing, you save nothing. This is truly the moment of truth for the firefighter. It’s what we all joined up to do. No one ever became a hero protecting exposures. No one ever received a medal of valor operating a deck gun or a ladder pipe.

This is why we need to be absolutely aware of the passage of time. When we make the choice to go in for whatever reason, the fire will continue to grow according to the laws of combustion, and the building will become increasingly dangerous with each passing minute until we get control or get out.

The Golden Hour that trauma victims have to survive is a luxury that firefighters on a structure fire can only dream of having. Diamond Time has four lines of continuity. The diamond starts with zero at the base and extends 10 minutes in two directions. The left-hand line indicates the possible survival of those trapped; the right-hand line indicates firefighting crews’ ability to get control. As each minute passes, the lines automatically extend in opposite directions. In other words, if you can’t achieve visibility and gain control of the fire, the chances of survival for occupants are affected.

The importance of these time frames has been recognized by some fire agencies. Fire Chief Don Oliver in Wilson, N.C., has a five-minute notice system in place in his communication center. His dispatchers are required to transmit a notice for every five minutes of elapsed time to the incident commander. If the IC receives the first notification and is still in the size-up stage, the problem is going to get a lot worse before it gets better. If the IC receives six such notices and crews are still unable to achieve entry and control, the problem is really serious.

The Diamond Time theory does not say that all fires will be controlled in 10 minutes. To the contrary, the theory recognizes that there are fire control times that go into hours, even days. When that happens, losses of life and property will increase. Moreover, danger to firefighters will continue to increase as the reasons why a firefighter can be injured or killed increase by order of magnitude.

Again, comparing the Diamond Time to the Golden Hour, one can easily recognize that there’s a point on the time line of providing medical care when a coroner is going to be more important than a paramedic. Well, there’s a point in time of a structural fire when a bulldozer and a scoop shovel are more important than a nozzle and a chain saw.

Rexford Wilson, clear back in the 1960s, wrote an article in an NFPA publication called Time — Enemy or Ally. Later that article was updated and published as Nine Steps from Ignition to Extinguishment. What seems to be the problem is that several generations of fire officers have failed to remember his basic warning: Time is really a vicious enemy on the fireground.

Maybe we have focused on the pre-arrival aspects such as response time without truly exploring that most important period that really creates results. On-scene performance is what firefighting is all about!

Want to be a hero? Get there on time to go in, get the people out so they can personally thank you for your courage, and put the fire out while it’s still confined to the room of origin. I may be wrong, but this is truly the most critical aspect of our job. Saving lives without giving one up, especially a firefighter’s.

So far, so good, I hope. If you can accept this theory, perhaps you can use it to your advantage, to your personnel’s advantage and to the advantage of the fire service. Start by developing a healthy respect for Diamond Time. Give it as much ink as the Golden Hour. Use it in explaining what a fire department does when it’s called to a structure fire. Make sure both your personnel and your stakeholders understand its importance.

Practice it on the fireground. If you’re the fire chief, expect your subordinate leaders on the fireground to respect the diamond. Make it your practice to talk about time frames in critiques. Measure time frames when you can. I will guarantee that more fires will have satisfactory outcomes if they are handled with one or two 10-minute periods, versus those that take 10 or 12. Use Diamond Time to indicate in your jurisdiction that you’re focusing on results, not the frequency of fires, and use it to justify your organization’s contributions to the community’s quality of life.

Many years ago I wrote an article describing the various “eras” of a fire’s growth. I proposed that we need to staff based on outcomes of the era that will result in the most likelihood of protecting our citizens and their property. In that matrix I was noted that if fires are handled when they are still at the point of origin, area of origin or even room of origin, things can be expected to be more satisfactory than when the fire is at the flashover stage or has taken the entire building of origin.

Recently, we have really managed to make the fire service pay a lot of attention to the cascade of events that has an effect our companies getting to the scene. Now let us concentrate on that first burning period after arrival. We need to simplify the science of firefighting into that period when we can make the most difference — Diamond Time.

Diamonds aren’t just a girl’s best friend, they are also a symbol of how precious life and property are, and even the smallest diamonds can make for the most precious fight we can give our community and the families of our firefighters.

I told you it was an “oldie but goodie,” right?

About the Author

It was with great sadness that the Coleman family shared that Chief Ronny J. Coleman, State Fire Marshal, (Ret.), passed away peacefully on September 19, 2023, at Mercy General Hospital in Sacramento.

Chief Coleman was a 50-plus year veteran of the fire service. Following his service and leadership as the Fire Chief in San Clemente, California, and the Fire Chief in Fullerton, California, he was appointed as California State Fire Marshal from 1992 to 2000 by Governor Pete Wilson. Chief Coleman was the past President of the International Association of Fire Chiefs and has been a member and leader of numerous fire service committees and associations.

He has given us all an incredible legacy with his dedication to our training and education. He championed the California State Fire Training system both as the Division Chief and has the Chairperson of the Statewide Training and Education Advisory Committee. He authored more than 19 books and was influential within our industry as an advisor, leader, mentor, and friend.

Fire & EMS Leader Pro The job of old firefighters is to teach young firefighters how to become old firefighters!

Fire & EMS Leader Pro The job of old firefighters is to teach young firefighters how to become old firefighters!