By: Robert Avsec, Executive Fire Officer

This year’s wildland fire season has been one of the worst in history for the western USA and Canada. Especially hard hit have been Washington State in the USA and the western provinces of British Columbia and Saskatchewan in where the scope and magnitude of this year’s fires has prompted the Premieres of both of those provinces to call upon Canada’s federal government to consider a national approach to fighting forest fires, fearing this year’s wildfires are the new normal.

I’ve just completed reading a fascinating book entitled, The Big Burn: Teddy Roosevelt and the Fire That Saved America, written by Timothy Egan (who also authored The Worst Hard Time, a book about the environmental disaster of the Dust Bowl in the mid-western USA in the 1930’s). Reading Egan’s rich narrative style of historical writing (one of my favorite genres) I learned 100% of what I’d previously not known about the worst wildfire in U.S. history: a fire that destroyed 3 million acres of national forests in the states of Washington, Idaho, and Montana on August 20, 1910 (For some perspective, the area of devastated land and towns equated to the size of the state of Connecticut).

The story chronicles the origins of the U.S. Forest Service and the rise of conservationism—setting aside forested

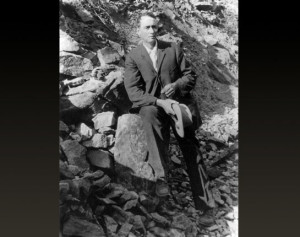

U.S. Forest Service Ranger, Ed Pulaski, one of the heroes of the “Big Burn of 1910”. He later invented the wildland firefighting handtool that bears his name.

lands as national forests to preserve them for future generations of Americans—and the origins of the U.S. Forest Service’s philosophy and policies regarding fires in national forests, both which still drive that federal agency to this day.

The “Big Burn” demonstrated with tragic results that that philosophy—stop all fires—which originated under our nation’s first Chief Forester, Gifford Pinchot, was completely at odds with Mother Nature. Despite the heroic efforts of a small number of forest rangers and an ad hoc collection of several thousand “firefighters”(pretty much anyone that could be found who was willing to join the effort) the fire storm brought hurricane-force winds to the mountains that literally blew over hundred-year-old trees in its path before incinerating everything in sight. One hundred of those brave souls would lose their lives in the failed effort.

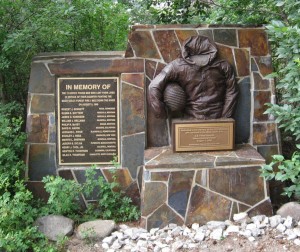

Memorial to those smokejumpers who lost their lives in Mann Gulch Fire, 1949.

Yet, one year after the fire Bill Greeley, a regional forester handpicked at the time by Pinchot, rose to a leadership in the U.S. Forest Service—with the full backing of the federal government—vowed that fire would never win again. This philosophy—which continues to be embodied by both the U.S. Fire Service and the federal government to this day–would shape U.S. Forest Service policy for the next 100+ years.

“Building on Greeley’s edicts on fire prevention, the Forest Service launched an even more demanding new policy in 1935, the “ten o’clock rule. Thereafter, any fire spotted in the course of a working day must be under control by ten o’clock the following morning.

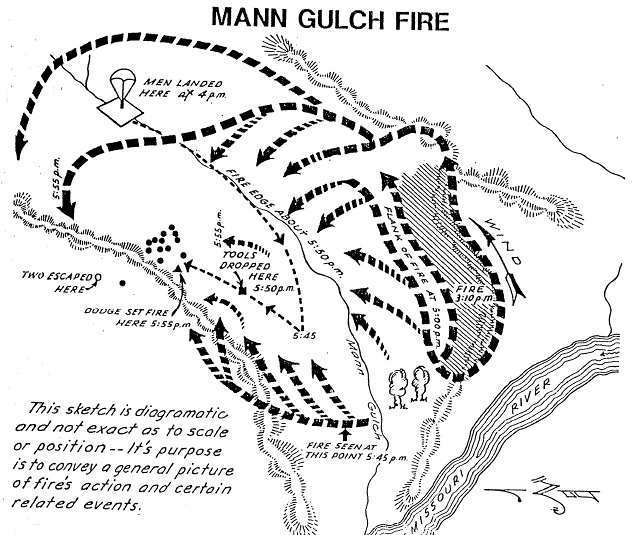

It was a losing and futile idea; in practice it became fatal. On August 5, 1949, a crew of fifteen smokejumpers leapt from a plane into a burning mountainside in Mann Gulch, Montana, acting on the ten o’clock rule. Less than two hours later, all but three of them were dead or fatally burned.– Timothy Egan in The Big Burn: Teddy Roosevelt and the Fire That Saved America

And it’s also become the expectation of the American public as well, particularly for those who choose to live in and

Remains of smokejumpers killed in Mann Gulch Fire being removed from the mountain.

around our national forests and in other wildland urban interface (WUI) areas of the country. People expect that firefighters will risk their lives to save them and their property even in the face of an overwhelming foe.

Wildfire experts are telling us that fires are burning hotter and faster and being feed by fuels—trees and vegetation—that in most western states have been ravaged by drought and insect infestation. Yet people still build in the WUI, fail to take appropriate measures when building their homes and maintaining their property and then expect firefighters to come to the rescue when wildfires strike (The vast majority of which are the result of lightning strikes that are part of nature’s cycle of death and renewal for forests).

This year the U.S. Forest Service has spent half of its annual budget fighting wildland fires; estimates provided by the service indicate that the amount could rise to two-thirds or more in the next ten years. These expenditures for fire suppression are having a severe drain on the service’s fire prevention efforts, e.g., vegetation and watershed management and land management planning, precisely the kinds of activities that could be reducing the available fuel loads in forested areas.

Fire & EMS Leader Pro The job of old firefighters is to teach young firefighters how to become old firefighters!

Fire & EMS Leader Pro The job of old firefighters is to teach young firefighters how to become old firefighters!