By: Robert Avsec, Executive Fire Officer

My late wife—and by proxy me as well—was a huge fan of the crime procedurals that have dominated television in recent years, (e.g., Law & Order, NCIS, CSI, Criminal Minds). A common theme we would hear every week is one of the characters telling one of their colleagues (who’s usually letting some emotion get in the way of logic), “Follow the evidence.”

How well are we in the Fire & EMS business doing at “following the evidence”?

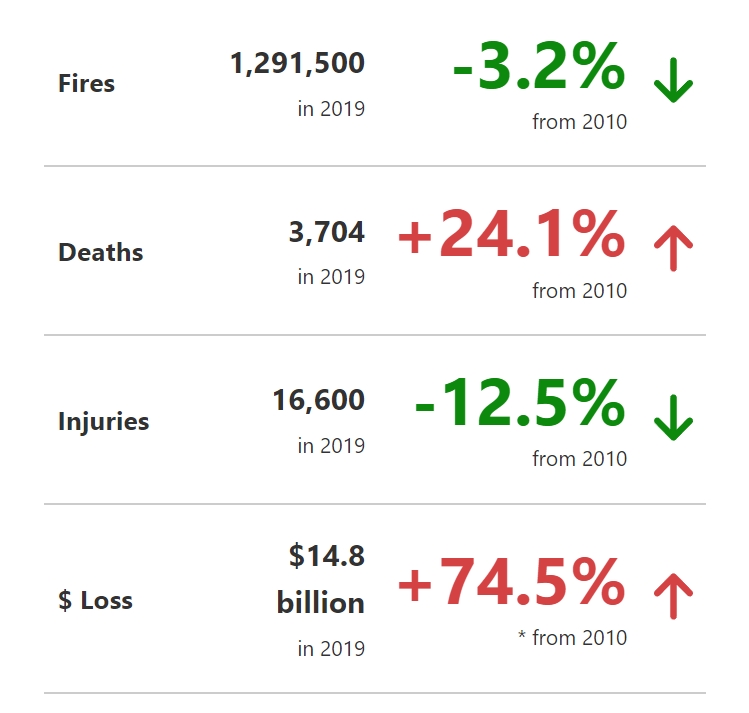

According to U.S. Fire Administration (USFA), between 2006 and 2015, the U.S. had an annual average of 1,398,000 fires resulting in 3,180 civilian deaths, 16,700 civilian injuries, and $14 billion in direct property loss each year.

In terms of estimates of fires, fire deaths and fire injuries, the estimates are lower than they were 10 years ago. When the USFA was established in 1974, annual fire deaths were estimated at 12,000. The goal then was to reduce deaths by 50 percent within 25 years; that goal was met.

By 2012, estimates of civilian fire deaths were at their lowest level (2,855). While fire deaths are still trending downward, in 2015, estimates of fire deaths were 15 percent higher than they were in 2012.

So, What Should We Do?

For starters, we must realize that we cannot eliminate fires, and the resultant deaths and injuries, completely. Not going to happen. At least not until we identify the “stupid” gene in people that leads them to do incredibly dumb things that cause fire. There, I said it. (To quote one of my favorite comics, Ron White, “You can’t fix stupid!”).

In the 1960’s, our society finally had enough of the deaths and destruction from automobile crashes on the highways and by-ways of America. In 1960, unintentional injuries caused 93,803 deaths in the U.S.; 41% were associated with motor-vehicle crashes. In 1966, after Congress and the general public had become thoroughly horrified by five years of skyrocketing motor-vehicle-related fatality rates, the United States Congress—which used to do its job in things like this!—passed the Highway Safety Act that created the National Highway Safety Bureau (NHSB), which later became the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA).

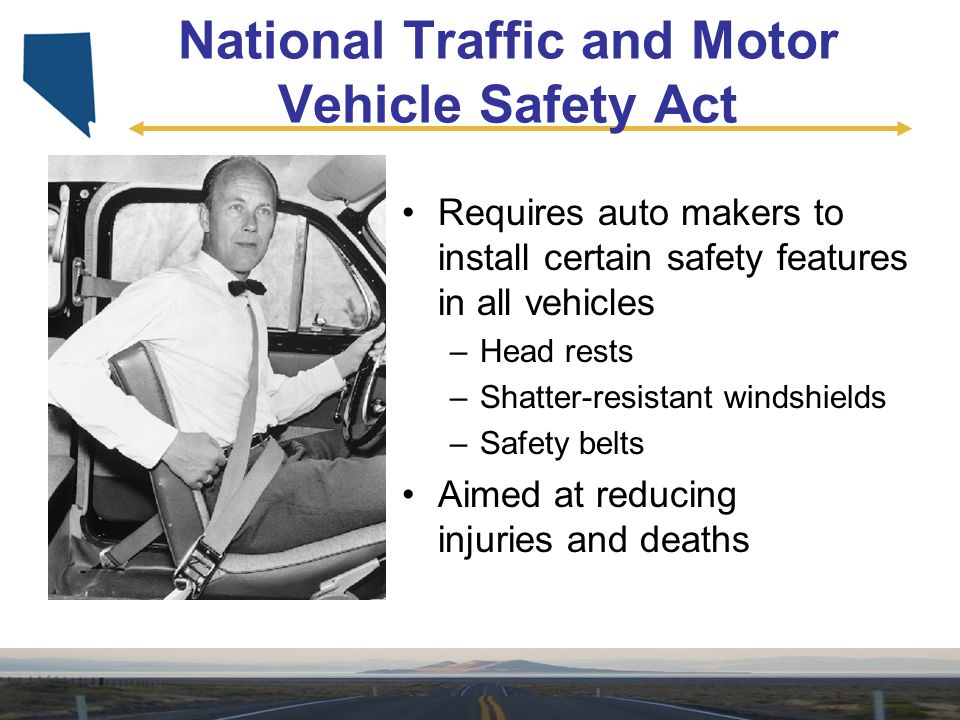

The National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act was enacted in the United States in 1966 to empower the federal government to set and administer new safety standards for motor vehicles and road traffic safety. The Act created the National Highway Safety Bureau (now National Highway Traffic Safety Administration). The Act was one of a number of initiative by the government in response to increasing number of cars and associated fatalities and injuries on the road following a period when the number of people killed on the road had increased 6-fold and the number of vehicles was up 11-fold since 1925.

The reduction of the rate of death attributable to motor-vehicle crashes in the United States represents the successful public health response to a great technologic advance of the 20th century—the motorization of America.

How did it happen? We took a systematic approach to solving the problem that resulted in changes such as:

- Birth of the modern trauma care and the Emergency Medical Services in the United States;

- Engineering changes to automobiles to protect occupants: lap/shoulder belt restraint systems; air bag restraint systems; energy-absorbing steering columns; vehicle chassis construction that dissipates crash energy to protect vehicle occupants;

- Improved road construction design that included: guard rails to prevent vehicles from striking stationary objects (e.g., bridge abutments) and vehicles from leaving the road (e.g., tight curves, and crossing into on-coming traffic).

So Why Aren’t We Taking the Same Approach to Preventable Fires?

If we took the same approach to reducing the number of fires and their impact on our society, we’d push for changes like these:

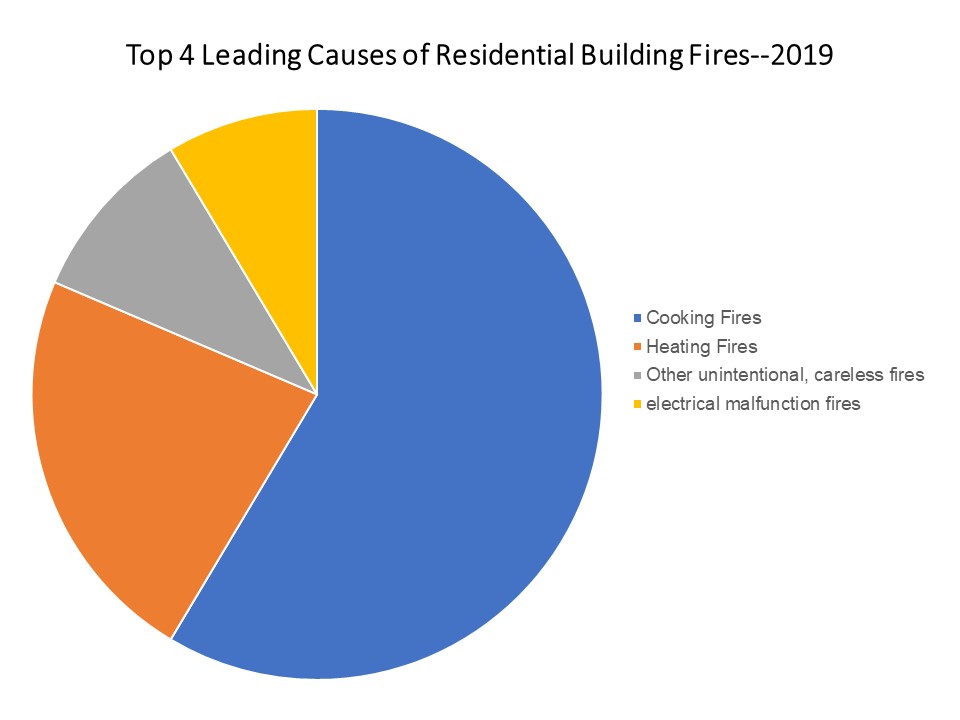

Action Item: All residential cooking equipment manufactured and installed in homes would come equipped with a fire suppression system installed, e.g., a hood suppression system. That system would also shut down the fuel supply to the equipment upon activation of the system.

Impact: The greatest source of fires, in the most frequent location of origin (42%), would be “stopped in its tracks”: (1) in its incipient stage before it could spread; and (2) occupants would not be injured (37% of fire injuries) attempting to extinguish the fire or attempting to remove a burning pot from the stove.

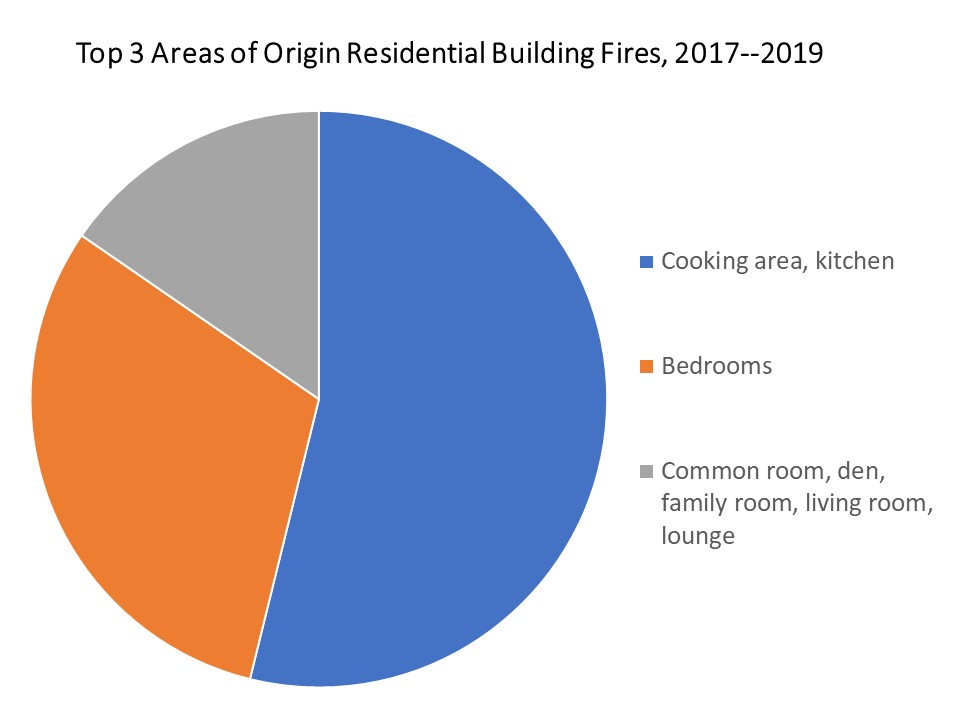

Action Item: Require the installation of partial residential sprinkler coverage in all living areas (living room, family room, and den) and in all bedrooms.

Impact: Fires would be controlled in their incipient stage in the residential areas that account for the greatest percentage of civilian fire deaths (combined 49%) and second leading area for civilian fire injuries (combined 33%).

These are just two that immediately come to mind when looking at the stats in Figures 1 and 2 above. But if we could be successful in doing this, in a generation or two we could have a substantial positive impact on:

- The Number of Fire that occur in kitchen/cooking areas and living areas);

- The Number of Civilian Fire Deaths (64% that occur in kitchen/cooking areas and living areas); and

- The Number of Civilian Fire Injuries (68% that occur in kitchen/cooking areas and living areas.

Sound rather harsh? Sound unrealistic? Consider for a moment what has happened since 9/11 to fight the “war on terror” — creation of DHS and TSA, hundreds of billions of dollars spent, laws adopted and changed, new training, new equipment, and new ways to do our jobs. With all that and more, we’ve not suffered a single terrorist-related death or injury on United States soil since that day. We have, however, lost a “city” of 30,966 people (total U.S. fire deaths for 2002-2011) in that same period.

Something to think about, no?

References

Federal Emergency Management Agency, United States Fire Administration, National Fire Data Center. http://www.usfa.fema.gov/statistics/reports/casualties.shtm

Federal Emergency Management Agency, United States Fire Administration, National Fire Data Center. Fire Death Rate Trends: An International Perspective. http://www.usfa.fema.gov/downloads/pdf/statistics/internat.pdf

Accidental Death and Disability: The Neglected Disease of Modern Society (1966). http://www.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=9978&page=11

Fire & EMS Leader Pro The job of old firefighters is to teach young firefighters how to become old firefighters!

Fire & EMS Leader Pro The job of old firefighters is to teach young firefighters how to become old firefighters!