By: Robert Avsec, Executive Fire Officer

I just read Chief Marc Bashor’s article, From ‘Black Sunday’ to Baltimore tragedy: January fires evoke pain, old and new. Is it just my observation—or just my perception—that we’re hearing about more firefighter maydays, more often?

If so, is it because more firefighters have become knowledgeable, skilled, and practiced with recognizing when they’re “in a jam” and declaring a mayday? (That would be a good thing!) Or is it because firefighters are getting into, or being placed in, situations that are “primed” for a mayday event to happen? (That would be a terrible thing!).

For the latter, I’m reminded of the words of the late Francis Brannigan, the “godfather of building construction, and its implications for firefighting strategy and tactics.” In his book, Building, Construction for The Fire Service,” Brannagan wrote (I’m paraphrasing somewhat):

There’s a difference between fighting a fire in a building and fighting a structure fire. In the former, the integrity of the building is sufficiently intact, making it possible to deploy firefighters and equipment to engage the fire inside the building safely, effectively, and efficiently.

In the latter, the fire is taking a toll on the load-bearing structural members and degrading the structure’s ability to resist gravity and that’s a situation that’s “primed” for a structural collapse.

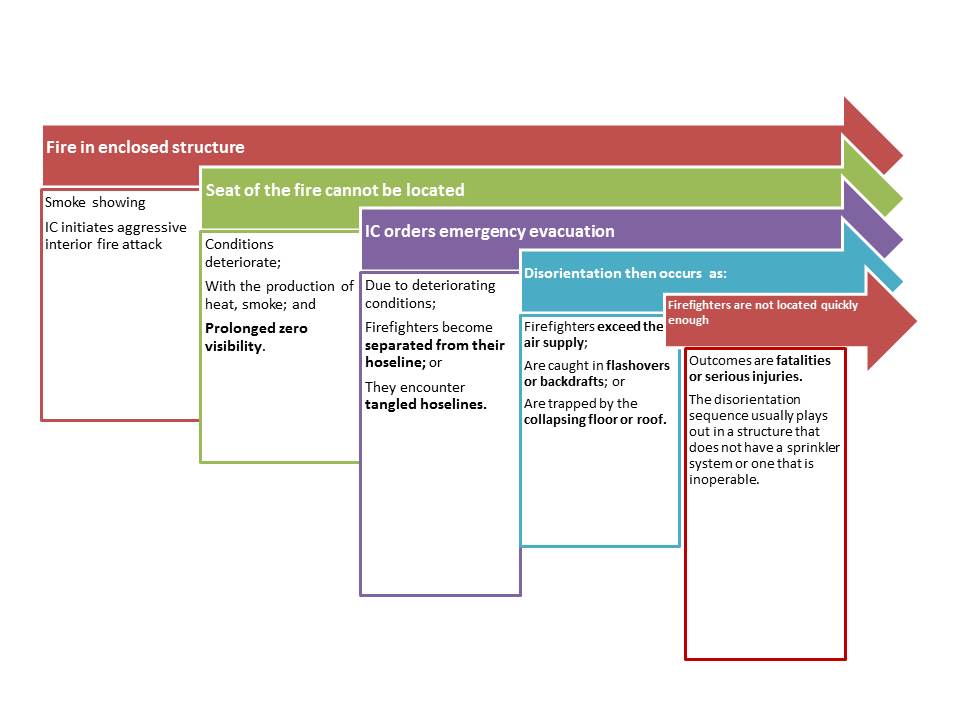

Another potential Mayday situation comes into play when firefighters are engaged in interior structural firefighting in smoky conditions (low visibility). Firefighters are at risk of becoming disoriented in such an environment. That’s just one of the “mayday situations” described by Dr. Burt Clark in his book, I can’t save your life, but I’ll die trying, that involve a firefighter becoming disoriented while working in low visibility conditions.

You’ve become disoriented or confused inside a structure within an IDLH environment and are no longer sure where you are or where the exit is located because you have lost contact with your crew, your hose line, or your lifeline (the rope variety) and you cannot reconnect within 30 seconds.

Recently, FireRescue1.com released a free eBook for download entitled, Your Mayday Survival Guide. The book has four articles that look at firefighter mayday events from different perspectives:

- Mayday, I’m Trapped in the Basement: Lessons Learned from My Mayday Experience, by Steve Conn, battalion chief and PIO for the Colerain Township (Ohio) Fire Department.

- Back-to-Basics RIT Training: Real-life mayday rescues need common sense and simplicity, not complexity, by Chris DelBello, senior captain for the Houston (Tex.) Fire Department.

- Learn To Command a Mayday Event, by Vincent Bettinazzi, a battalion chief with the Myrtle Beach (South Carolina) Fire Department.

- The Portable Radio: A Firefighter’s Other Mayday Lifeline, by Robert Avsec, battalion chief (Ret.), Chesterfield (Va.) Fire and EMS Department.

Mayday Procedures

Does your fire department have a written firefighter mayday procedure (SOG)? If not, you should be asking why not?

If it does, how skilled and practiced are you and your peers at following the procedure in the event you find yourself in a mayday situation?

One of my favorite axioms from noted public safety risk advocate, Gordon Graham, is “Predictable is preventable.” And we’re learning that Mayday events can somewhat be predicted because of what’s been learned and continues to be learned by the Mayday Project.

Did you know that many maydays occur between midnight and 3:00 AM? That’s just one of the “nuggets of information” about firefighter maydays that we’ve learned that from the Mayday Project.

Read Next: Maydays, Rapid Intervention Operations in Structural Firefighting and NFPA 1407

Mayday Procedures for Firefighters

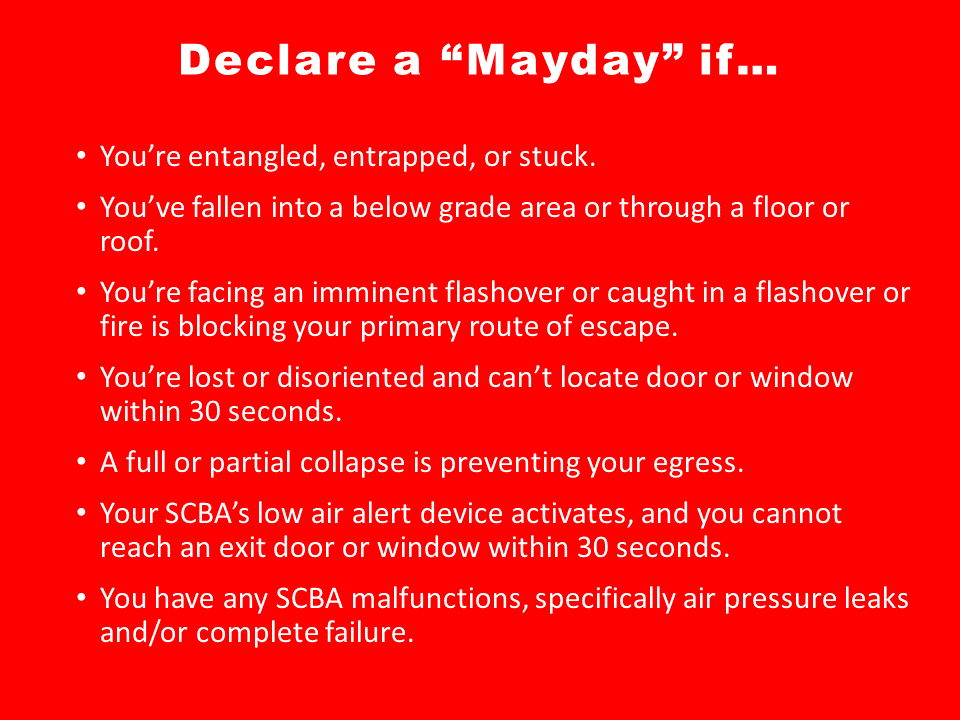

Your fire department’s Firefighter Mayday Procedure (or SOG) should clearly state those situations where, according to Dr. Clark, a firefighter must declare a Mayday:

- You’ve fallen through a roof, through or down a set of stairs or through a floor.

- Your primary exit is blocked by any type of collapse, and you cannot reach a secondary exit within 30 seconds.

- You are caught in a flashover condition or recognize that a hostile fire event is about to occur, or if your primary exit is blocked by fire.

- You’ve lost your mobility for any of these reasons—entanglement, trapped, pinned, stuck, caught, or wedged—and cannot extricate yourself within 60 seconds, OR your SCBA low air alarm activates WHILE you are trying to extricate yourself from one of these situations.

- You’ve become disoriented or confused inside a structure within an IDLH environment and are no longer sure where you are or where the exit is located because you have lost contact with your crew, your hose line, or your lifeline (the rope variety) and you cannot reconnect within 30 seconds.

- Your SCBA’s low air alert device activates, and you cannot positively reach an exit door or window within 30 seconds.

- Your SCBA malfunctions or you have difficulty with maintaining proper operation of your SCBA for any reason while operating within an IDLH environment.

- You are operating within an IDLH atmosphere, and you become injured or sick and your crew mates cannot safely assist you out of the building immediately.

Next, the procedure must describe exactly the actions that the firefighter must follow after they declare a Mayday to aid the IC in locating them and directing rescue resources to their location. The following are two of the commonly used reporting formats in use by fire departments:

LUNAR

L-Location. Where are you geographically within the structure or event?

U-Unit. What company are you or were you with?

N-Name. Communicate your name, preferably your last name not your fire number.

A-Assignment and Air Supply.

R-Resources needed to help and rectify the problem. Also communicate what you are doing to rectify the problem.

Example: “Command from Mayday firefighter. This is Firefighter Adams with Engine 14. I’ve fallen through Floor 1 into basement. I was advancing hose line with Engine 14. I have 900 psi of air left. My left leg is broken.”

LIP

L-Location. Where are you geographically within the structure or event?

I-Identification. This includes your last name, the company you were with, and your assignment.

P-Problem. This includes resources to assist and rectify the problem, your air supply and what you may be doing to rectify the problem.

Example: “Command from Mayday firefighter. I’ve fallen through Floor 1 into basement. I’m Firefighter Adams, Engine 14. We were advancing hose line to fire room. My left leg is broken and I have 900 psi of air left.”

The Mayday procedure should also provide those actions that the incident commander must follow after a mayday. Firefighter maydays declared. Those actions should include

- Deploying the RIT

- Keep firefighters who declare my mayday on the same radio channel and maintain voice contact.

- Move all the other operating units, including the RIT, to another radio channel.

- Appoint Operations Section chief to continue fire suppression work.

- Gather LUNAR information from firefighter who declared Mayday.

- Coordinate with the Operation Section Chief to get necessary resources to the Mayday firefighter.

Developing “muscle” memory

In this case, I’m referring to your brain as a “muscle.” Gordon Graham would classify your department’s Mayday procedure as “high risk, low frequency, non-discretionary time (NDT)”; NDT means you must know what needs to happen and you must act now. No time to look it up on a computer or smartphone or in a reference book, and you must get it right every time

Company officers should make it a priority to review the Mayday procedures with their personnel in the evening before everyone starts heading for their bunks. Why then and not at the beginning of their tour of duty?

Because the data from the Mayday Project shows that most firefighter Maydays happen between 12:00 midnight and 3:00 AM. (Did you know that jet fighter pilots review the ejection protocol for their aircraft as one of their last activities before getting into the cockpit? True. In fact, it was the jet pilot injection protocol that helped Doctor Clark to develop the firefighter Mayday procedure. Right, Doc?)

For volunteer staff, fire departments make reviewing your department’s Mayday procedure a part of your regular training schedule. Make posters of your Mayday procedure and display them prominently within your fire station, especially in the apparatus bay (Come to think of it, that’s a great idea for all fire departments).

Practice, practice, practice

The legendary Green Bay Packers head coach, the late Vince Lombardi, said it this way, “Practice does not make perfect. Perfect practice makes perfect.”

For more on this, I highly recommend reading the article, Back-to-Basics RIT Training: Real-life mayday rescues need common sense and simplicity, not complexity, from the FireRescue1.com eBook, after you download your copy, it’s great stuff.

Avoiding a Mayday Situation

An ounce of prevention is worth more than a pound of cure, right? The best mayday response is the one that never happens, so always:

- Conduct a 360-degree assessment of a structure fire before commencing any interior fire suppression activity.

- Always employ ICS at every call for service.

- Always maintain crew integrity.

- Tactical leaders (e.g., crew leaders, division or group supervisors) must consistently communicate with the IC (or operations chief or branch chief if activated) about what’s happening in their tactical area.

I like the CPR Report format: Conditions, Progress towards your assigned objectives, and Resource needs. For example:

“Command from Division 2. Made it to floor 2. We have heavy smoke, moderate heat. Need smoke removal from floor 2. We can make it to the fire room if we get that ventilation.”

It’s that sort of communication from all their tactical leaders that the IC needs to be able to evaluate how well their strategy is working. When the IC is seeing something from the outside that’s “not jiving” with what his people are telling him from the inside, it’s time to make adjustment in their strategy and often, that should mean getting out of the structure while it’s still standing.

And that’s something we can all get better at: deciding that being inside is no longer the place to be. Because architects and builders don’t design and build structures to resist fire. They built them to resist gravity, and that’s one law that’s absolute.

Fire & EMS Leader Pro The job of old firefighters is to teach young firefighters how to become old firefighters!

Fire & EMS Leader Pro The job of old firefighters is to teach young firefighters how to become old firefighters!