By: Dr. Will Brooks, Ed.D

I’ve been involved with firefighters and the stress reactions they experience for over 25 years, so the recent trend to using the PTSD (Post- Traumatic Stress Disorder) term for all manner of stress reactions causes me concern. There is no doubt that firefighters and other first responders do sometimes experience PTSD. It has been my privilege to listen to several first responders who could be accurately diagnosed with PTSD.

Traumatic Stress Disorder) term for all manner of stress reactions causes me concern. There is no doubt that firefighters and other first responders do sometimes experience PTSD. It has been my privilege to listen to several first responders who could be accurately diagnosed with PTSD.

However, recent articles and “studies” purporting to be seeing PTSD in groups of firefighters are alarming in the use of rates for this diagnosis. A quick sample of these efforts indicates ranges from 17-24% of a cohort of firefighters who could be said to have PTSD.

Please listen to the excellent BBC broadcast dealing with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. This 18-minute review, in my mind, puts the matter in a much clearer frame.

As well, I suggest reading Dr. Jacinthe Douesnard’s recent Canadian studies on the psychological health of firefighters. (Note: The website was created in French, but the Google Chrome browser will automatically translate the page’s text). She recently presented to the Canadian Association of Fire Chiefs and her work suggests a 1% rate of diagnosable PTSD in firefighters. (Dr. Douesnard has also authored a book on the subject of her research, The Emotional Health of Firefighters, that is available on-line from the Quebec University Press).

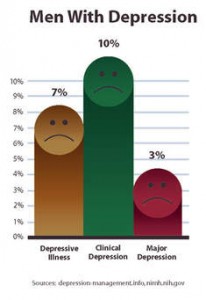

In both the above cited cases, rates of PTSD vary between 1 and 3%, a far lower number than that noted in the second paragraph. How could this be explained?

In the late 70’s through the 90’s and even to the present there has been the wide spread adoption of stress as it occurs in response to what became known as a critical incident. Critical Incident Stress (CIS) and its management became quite prevalent in first responder communities, and in many it still thrives.

In the late 70’s through the 90’s and even to the present there has been the wide spread adoption of stress as it occurs in response to what became known as a critical incident. Critical Incident Stress (CIS) and its management became quite prevalent in first responder communities, and in many it still thrives.

See Related: Developing a CISM team

But something shifted. The Middle Eastern wars in which both the U.S. and Canada have been engaged, rained down a continuous exposure to critical incidents and ongoing trauma. Unlike their civilian counterparts who could be involved in Critical Incident Stress Debriefings as needed, our military members had very few ways to carry on Critical Incident Stress Management given the potency of stressors and their continuous nature.

As we have learned from our veterans, there was a demonstrable lag between psychological injury and any type of diagnosis or treatment.  Despite the lag, however, our media and some military institutions began to recognize PTSD as a real entity. Because it was very slowly acceptable for members exposed to combat to suffer from PTSD, the label was adopted quite widely. There was no diagnostic criteria for CIS, only PTSD, in the 1980 edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) published by the American Psychiatric Association. Thus, if a member had any type of stress reaction or affective disorder, it was frequently presumed to be PTSD.

Despite the lag, however, our media and some military institutions began to recognize PTSD as a real entity. Because it was very slowly acceptable for members exposed to combat to suffer from PTSD, the label was adopted quite widely. There was no diagnostic criteria for CIS, only PTSD, in the 1980 edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) published by the American Psychiatric Association. Thus, if a member had any type of stress reaction or affective disorder, it was frequently presumed to be PTSD.

In my own experience, clinical depression continues to be the prevalent issue for firefighters. It can be part of the constellation of reactions to trauma and a diagnosis of PTSD, but often it is a stand-alone illness. The tragedy of a suicide is all too real among first responders. It could be said that some suicides occur in people with diagnosed PTSD, but many more arise from the unremitting horror of depression, the cause of which might not be any traumatic event at all.

In my own experience, clinical depression continues to be the prevalent issue for firefighters. It can be part of the constellation of reactions to trauma and a diagnosis of PTSD, but often it is a stand-alone illness. The tragedy of a suicide is all too real among first responders. It could be said that some suicides occur in people with diagnosed PTSD, but many more arise from the unremitting horror of depression, the cause of which might not be any traumatic event at all.

Again, let me repeat, PTSD can well be an accurate diagnosis in first-responders. But when the term PTSD is ubiquitous and synonymous with any stress reaction, its usefulness and accuracy is questionable. If the term PTSD is used in a specific firefighter’s situation, let’s be sure that the person has been accurately diagnosed by a competent mental health or medical practitioner and that the criteria for PTSD as outlined in the latest edition of the DSM have been met.

The human mind under all types of stress is a remarkable and complicated entity. Human beings have numerous ways of dealing with the  stresses they experience. Firefighters are like other humans, and they cope in ways about which, often, we know very little. It is no surprise to learn that firefighters experience both varying stresses, some extremely toxic and traumatic, and yet they display coping mechanisms which not only work but are effective and result in the individuals continuing to function both on and off the job.

stresses they experience. Firefighters are like other humans, and they cope in ways about which, often, we know very little. It is no surprise to learn that firefighters experience both varying stresses, some extremely toxic and traumatic, and yet they display coping mechanisms which not only work but are effective and result in the individuals continuing to function both on and off the job.

And let us continue to employ Critical Incident Stress Management in the most robust programs available where and when possible. To do less is possibly to short change our people and pave the way for more complicated mental health issues, e.g., an accurate diagnosis of PTSD, down the road.

Resources

Firefighter Behavioral Health Alliance

About the Author

Dr. Will Brooks has retired from more careers than most people ever become involved in, particularly in the fields of clinical psychology and post-trauma where he’s been an academic, a researcher, a debriefer (the Westray Mine accident, the sinking of the Cape Aspy and a mine collapse in Kentucky), a supervisor for candidate psychologists, and the chairperson for several psychological association committees (Ethics, and Post-Trauma Services).

Dr. Brooks also served as the Lead Consultant to Canadian Forces in developing the Member Assistance Program 1998-2000 and served as the Developer and Clinical Director of the Nova Scotia Firefighters Critical Incident Stress Management Program.

Dr. Brooks is a retired firefighter who was a Founder and President of the Canadian Fallen Firefighters Foundation. He’s written about firefighters and Critical Incident Stress and has presented his findings to fire service organizations, as well as private and public sector organizations, across Canada.

He now makes his home in Lunenburg, Nova Scotia with his wife, Cheryl (a retired Canadian Air Force Colonel who is also widely known as Cheryl D. Lamerson, C.D., Ph.D.) They have four adult children and five grandchildren that keep them busy in their “golden years.”

Fire & EMS Leader Pro The job of old firefighters is to teach young firefighters how to become old firefighters!

Fire & EMS Leader Pro The job of old firefighters is to teach young firefighters how to become old firefighters!