By: Robert Avsec, Executive Fire Officer

Source: www.tema.ca/home

There’s a great deal of discussion going on in social media, fire service trade journals (hard-copy and on-line editions) and at fire service conferences about the firefighter mental health problems that too many firefighters are struggling with. Increasingly, the adverse effects of post-traumatic stress (PTS) are manifesting themselves in a greater number of firefighters struggling with depression, PTSD, and too often, suicide.

Firefighter Suicide

On average, a firefighter takes his or her own life every 36-72 hours in the United States. Just yesterday, a fire service colleague shared with me that a student in their college-level fire administration program had committed suicide several days earlier. That firefighter left a spouse and five children. And an unknown number of family members, friends and colleagues who have been left wondering, “Why did this happen?”

Our Reactive Approach

Just last week, I attended my first meeting as a member of the Honorary Board of Advisors for Warriors Heart in Bandera, Texas (about 50 miles northwest of San Antonio). I wrote about that experience in this blog post.

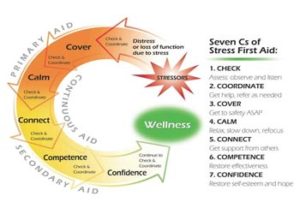

And while I know and understand the overwhelming need to give care and treatment for addiction and depression or PTSD resulting from PTS, I’m also aware of the fact that we’ve got to become more proactive in our efforts to develop emotional survivability in our men and women in the fire service

Canadian First Responders: See TEMA.CA, “Canada’s leading provider of peer support, family assistance,  and training for our public safety and military personnel dealing with mental health injuries.”

and training for our public safety and military personnel dealing with mental health injuries.”

Trust and Respect

One of my “take aways” from that first meeting at Warriors Heart was from the Clinical Director, Ms. Annette Hill, and her presentation on “why” and “how” the Warriors Heart treatment approach is so successful. Ms. Hill said it this way:

A soldier tells you, “I go to war so you don’t have to.” But if that soldier comes back from war and tells you about what it was like for them in combat, then they’ve brought you into the war. And for a soldier—to share the burden that they’ve taken on in your place—that’s unacceptable.

So, they keep those strong emotions and feelings of combat bottled up. And when that happens, those unprocessed effects of PTS can start a downward spiral into depression, addiction or PTSD.

But when that soldier is in a group of fellow soldiers—who’ve been there, seen it, and done it—soldiers struggling with the same depression or addiction that they are experiencing, they feel safe and secure. And only then do they “open up” and “download” their brain that’s jammed up with unresolved emotions and feelings caused by PTS. The things that drove them to seek comfort in drugs or alcohol.

Now substitute the word firefighter for soldier in Ms. Hill’s narrative. We do the job so that others don’t have to. We take a deep responsibility for making bad situations better. Listen to the words we use:

- We lost that house;

- I lost that child who drowned in the swimming pool; or

- We lost that mother and two children in that apartment fire.

We take on all that responsibility—and the emotions and feelings that go along with it—day in and day out. But who can we talk to about it to “download” our brain so that it doesn’t drive us to abuse drugs or alcohol or become depressed or develop PTSD? We typically don’t talk about it with our family or friends because subconsciously, “We don’t want to take them there.”

See Related: De-stigmatizing Post-Traumatic Stress by Annette Hill.

So, who can we talk to?

We can’t or won’t talk to mental health professionals. Why? Because, unless they’ve “been there, seen it, and done it”, they too are outsiders. And without that common ground, there’s never the trust and respect and understanding that gives us “permission” to open up

So, that leaves our colleagues in the fire station. But what’s the level of trust and respect and understanding in your fire station or within your department?

I read this piece just today on-line, Psychologists diagnose what ails Clearwater Fire and Rescue. I urge you to read it  as well because I see a direct linkage between the level of everyday trust and morale in a fire and EMS department and the ability for its members to “be there” for one of their own who’s struggling with PTS.

as well because I see a direct linkage between the level of everyday trust and morale in a fire and EMS department and the ability for its members to “be there” for one of their own who’s struggling with PTS.

If we’re to be successful in becoming more proactive in our efforts to protect our people from the emotional toll that our profession can take on firefighter mental health, shouldn’t we be taking a good hard look at the one place that they should feel safe, secure, and respected, the fire station?

There are likely a great many things that we could start doing to become more proactive in helping our men and women in the fire service to avoid becoming “mental casualties of the job.” I’m not sure yet what some of those might be, but I’m confident that through my association with the great people at Warriors Heart, like Annette Hill, that I’m going to learn what they could be.

Fire & EMS Leader Pro The job of old firefighters is to teach young firefighters how to become old firefighters!

Fire & EMS Leader Pro The job of old firefighters is to teach young firefighters how to become old firefighters!